This week the ALPHA collaboration had our paper “Antihydrogen accumulation for fundamental symmetry tests” published in Nature Communications. I’m proud to be listed as an author!

Our collaboration studies antimatter, specifically, antihydrogen (the simplest antiatom). We measure its properties to high precision so we can compare it to “regular” hydrogen. This comparison allows us to test fundamental symmetries that are a cornerstone in modern physics.

The research problem

Both matter and antimatter must be identical in every way, except that their intrinsic quantum numbers will be equal and opposite in sign. For example, electric charge is a quantum property, so an electron has a negative charge (e–) and a its antimatter counterpart, the positron, has a positive charge (e+). So far, experiments agree with theory: atoms and antiatoms have identical mass, magnetic moment, and internal structure.

The search for hints about why there’s more matter than antimatter in the universe (the asymmetry problem) is still ongoing. There are still more comparisons to be made! The next test the ALPHA collaboration will perform is to determine how antimatter interacts with gravity.

One of the limiting factors in studying antihydrogen is that it’s difficult to create cold (low kinetic energy), ground state antihydrogen atoms. Very little cold antihydrogen is created each time you try to make it, or each “cycle.” Our collaboration has led the way in creating and holding onto it since they were the first to trap antihydrogen in 2010.

The stacking paper

This new paper describes a procedure to increase the number of antiatoms trapped and detected each cycle – an order of magnitude improvement over previous work. Through fine control of plasmas of electrons, positrons and antiprotons, it’s possible to synthesize and trap antihydrogen atoms repeatedly, while at the same time holding onto atoms produced in previous cycles. This is a process we call “stacking.” We accumulate antihydrogen atoms before running our tests so we can use them in larger numbers. This ensures a greater chance of success each time we attempt a measurement.

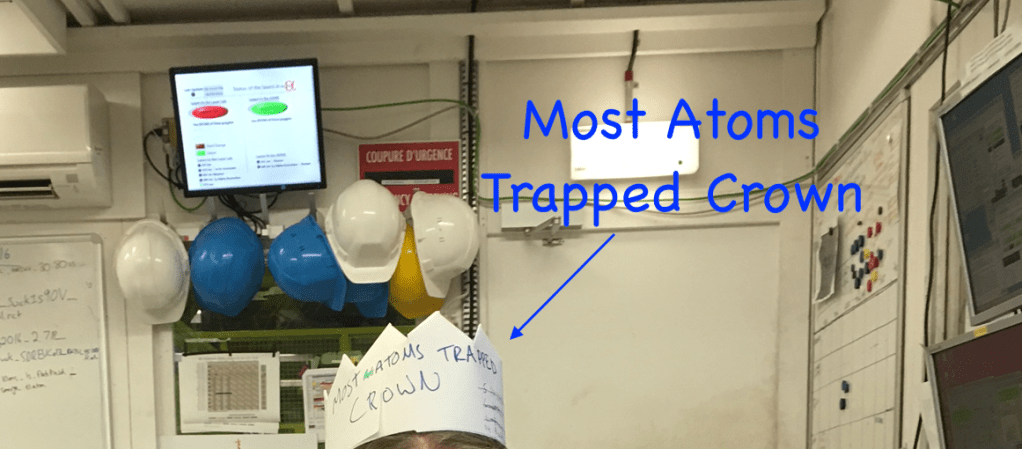

While we were completing this work, every time a new record was set for detected annihilation events (revealing how many antiatoms were accumulated), the person running the main control system received the coveted “MOST ATOMS TRAPPED CROWN.” The rest of the collaboration was notified with an email titled “Long live the queen.” The record for detected annihilation events from a single release of trapped antiatoms at the time of publication is 54, after five cycles of stacking.

Now that we can trap more antimatter, we can make statistically significant measurements faster, and we are better poised than ever to find an answer to the asymmetry problem.